When I was at high school and was required to read books by Jane Austen I did my best to find them interesting but failed dismally. The characters and situations she describes in her novels are very far removed from any situation I had ever experienced, and the idea that a young woman’s sole purpose in life was to find a wealthy husband seemed too feeble to be considered a suitable reason for existing. I was too involved in the ups and downs of my own twentieth century life to appreciate the limitations and concerns that overshadowed the way women lived in the eighteenth century, and I failed to perceive Austen’s perceptive analysis of human behaviour, and the manners and mores of her time.

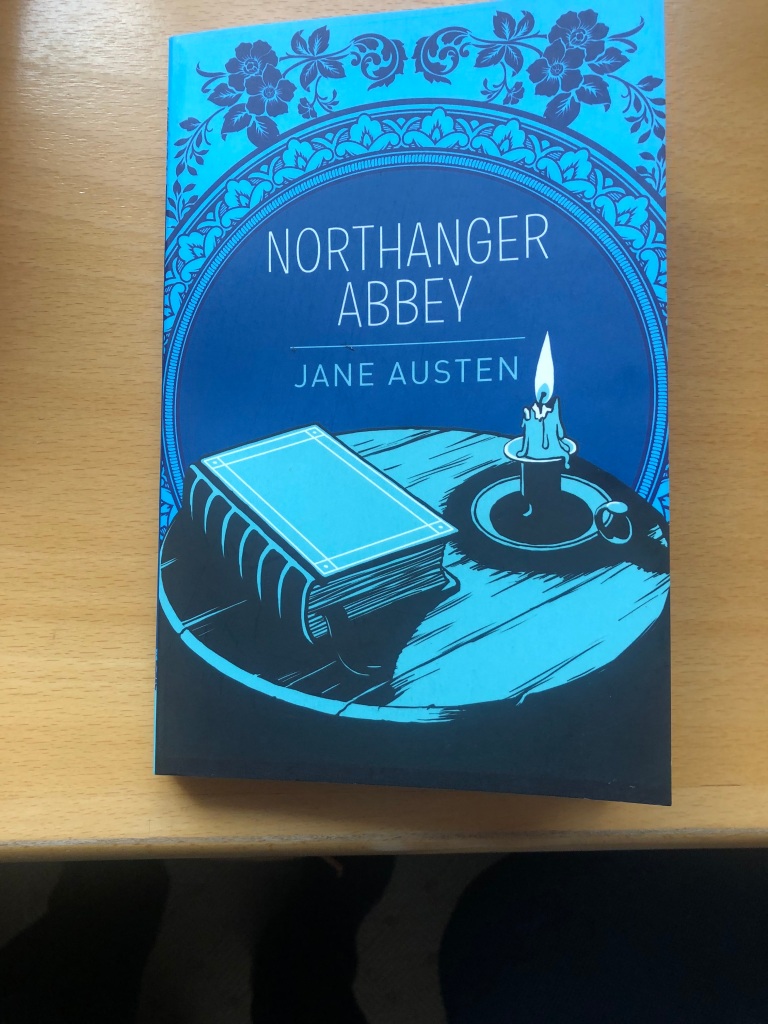

So it was with suspicious curiosity that I embarked on reading one of Jane Austen’s later novels, one I had not been required to read while at school, ‘Northanger Abbey.’ The first half of the book describes in great detail the experiences of a young woman being entertained in the fashionable town of Bath, where life consisted of balls and social occasions of various kinds. The heroine of the book, Catherine Morland, is described as an innocent young woman who is eager to enjoy all the delights of fashionable society, while at the same time being unduly influenced by the lurid novels she reads. In fact, what Austen is doing here is poking fun at other – mainly female – writers, like herself, and especially at the tendency of young readers to let their imagination run away with them.

Thus, while staying with newly-acquired friends at their home, the Northanger Abbey of the title, Catherine imagines that all kinds of strange and wonderful events have taken place there, and even comes to the conclusion that the father of her friends has locked his wife up, or even murdered her – shades of Charlotte Bronte’s novel, ‘Jane Eyre’ (which was published several years later). On one level, the book is a homily on the way young women’s minds could be manipulated by novel-writers, and on another it is a parody of that self-same kind of book.

Naturally, as in every self-respecting novel, there must be the aspiration for love as well as disappointment in that sphere, in addition to entertaining encounters between clever young men and innocent young women, where in some cases the former poke fun at the latter, or in others seek clumsily and unsuccessfully to curry favour with them. Financial prosperity also plays a part in the way the characters relate to one another, and it is only at the very conclusion of the book, after innumerable ins and outs as well as ups and downs, and even a heart-stopping contretemps just before the end, that all ends well.

Setting aside the narrative style that Jane Austen adopts, which is inevitably coloured by the narrative conventions and speech patterns of the time as well as her own inimitable turn of phrase which even involves direct interaction with the reader, one cannot avoid admiring her ability to create credible characters, each with their own way of speaking, thinking and acting. It is not for nothing that her books, though limited to a time and society that is long gone, have endured for so many years, and today are considered classics of the genre.

I only vaguely remember this book. In general I think Austen’s themes are still relevant… the search for love and the outing of pretentiousness.